Bony Ramirez: Reimagining the Caribbean Body

by Leticia Sanchez Garris. Images Courtesy of the Artist. Photo by Elianel Clinton

In this conversation with writer Leticia Sánchez Garris, Dominican-born artist Bony Ramirez reflects on spirituality, mythmaking, and the power of the Caribbean body. From his early days in Tenares to his rise on the international stage, Ramirez reimagines the symbols, textures, and histories that define the Caribbean. His work transforms objects of struggle into icons of resilience—bridging ancestral memory with contemporary identity.

You grew up in Tenares, and before becoming an artist you wanted to be an altar boy (monaguillo). How do you remember that time? What led you from a space so deeply connected to faith and the church to expressing yourself through art? Do you feel that spirituality is still present in your work, even if through a different lens?

Yes, as a kid at some point I wanted to be an altar boy. I was fascinated by the respect and attention that certain roles received in the church, and that sense of reverence really drew me in. At the same time it became my first real exposure to art because in the Dominican Republic, it’s common to see murals both inside and outside the churches, and combined with the sculptures, images of Christ and the Virgin, and paintings, it was all incredibly inspiring and captivating to me. That influence has carried over into my practice today. My earlier influences were again the European painters of the Renaissance, as well as 18th and 19th century European painting. The way saints were depicted, the compositions, the visual storytelling. I still use many of those references, but I interpret them in my own way. That blend of spirituality, fascination with religious art, and interest in specific historical periods continues to shape how I compose and think about my work.

Migrating as a teenager often shapes how one sees oneself. How did that change of territory, language, and culture influence the way you represent Dominican identity and the Caribbean through your artistic practice?

I came to the U.S. when I was 13, which is that in-between age, those teenage years really stick with you. I still remembered a lot from the Dominican Republic, and being here felt almost 50-50, like half of me in one place and half in another. It made me really want to hold on to my memories from back home, and that definitely comes through in my work. I try to capture the traditions, the games, the things I did as a kid. It’s like keeping those younger years alive through my art. Now, having spent the same amount of time here as I did back in the DR, I’ve been thinking a lot more about the immigrant experience in the U.S., not just from a Dominican perspective but from a Caribbean perspective in general. That mix of experiences keeps shaping how I approach identity and culture in my work.

Your background in construction is evident in the textures and finishes of your pieces. In what ways does that technical knowledge influence how you create and choose your materials?

I think my background in construction has had a big influence on my work. During those years, I learned not just how to use tools, but also how to work with different materials. Even as a self-taught artist, my practice has always been about experimenting and seeing what works, and that experience gave me access to tools and materials that I’ve incorporated into my art over the years. Even if it was just in the back of my mind at the time, construction taught me a lot about problem-solving, both technically and practically, whether it’s cutting wood for sculptures or using nuts and bolts. Looking back now, I realize how essential that stage of my life was. I didn’t know then how much it would benefit me later, but it’s definitely shaped how I approach being a full-time artist today.

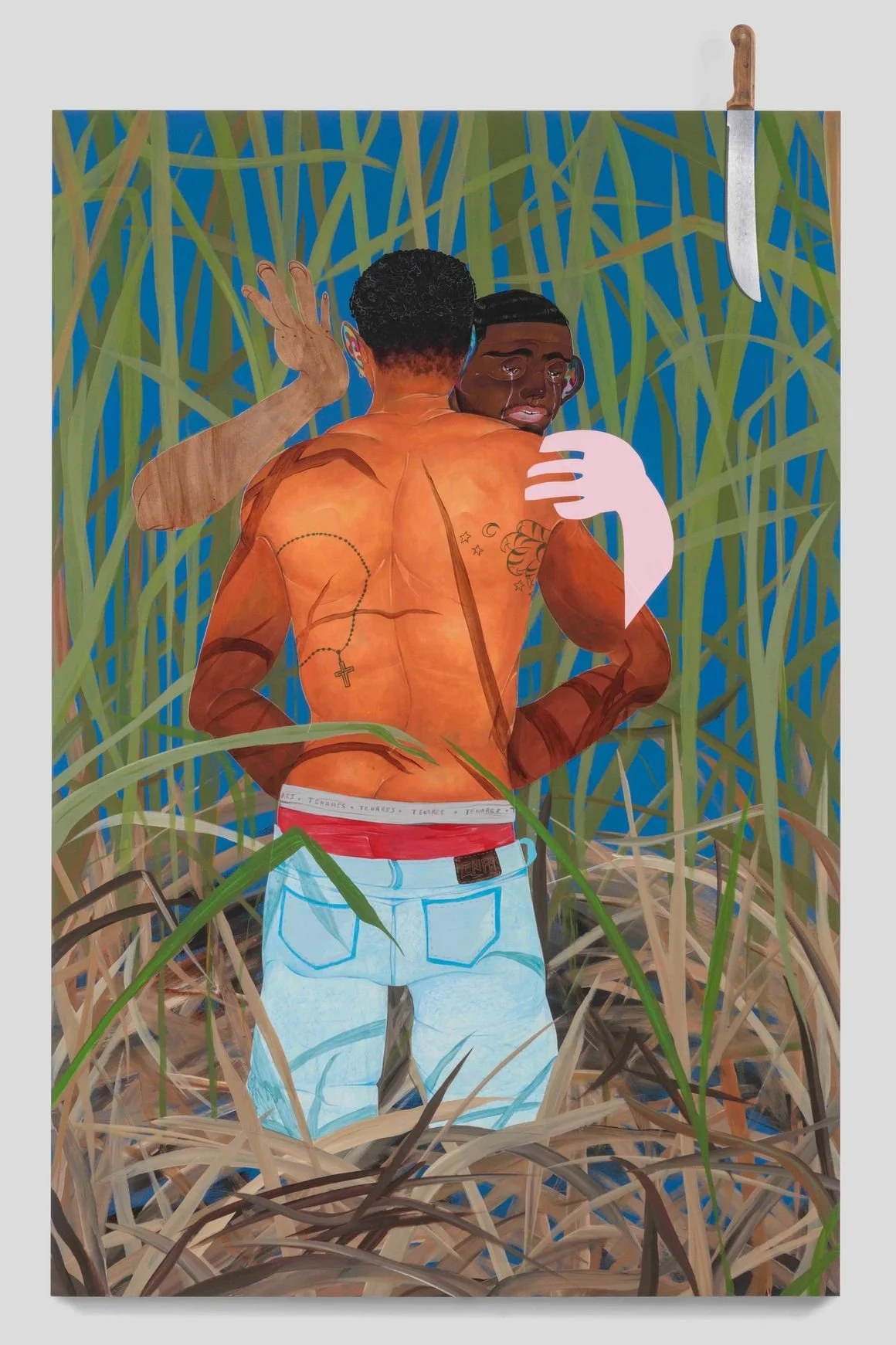

The machete appears throughout your work, transformed from an object often associated with violence into something poetic and beautiful. What does this process of re-signification mean to you, and how does it connect to the history of the Caribbean and the Dominican Republic?

Machetes have always been part of my work from the beginning. I see them as a symbol of liberation and strength, connected to the revolutions our country has had, including the Haitian revolution, and also to the people working in the fields in the Dominican Republic. For me, and historically, the machete symbolizes strength and resilience. It’s important to have this symbol in my work, especially in pieces with historical context related to the Caribbean. The fact that it is a weapon and a harvesting tool, essential for generations, and historically used by ancestors for revolution and change. This duality of strength and utility is part of many of my works.

Some of your pieces evoke mythological figures like the ciguapa, deeply rooted in Dominican folklore. What role does mysticism or mythology play in your creative process? What draws you to these beings that exist between the human and the spiritual?

In my case, I’m more interested in creating my own mythologies, though I am inspired by those that already exist in our culture. I’m especially drawn to the magical realism part of my work, where I can create figures that are not anatomically correct and often mix elements of animals, plants, and other forms, building their own worlds. I would say I am interested in creating my own mythologies and mysticism while being inspired by Caribbean and Latin American folklore. For me, it’s more interesting to explore magical realism by creating figures that combine different elements and exist between the human and the spiritual.

Your work blends religious symbols with ancestral energies. How do these two forces coexist within you? And by that I mean the religiosity you grew up with and the spirituality that now runs through your art?

In my case, there’s definitely a good balance of both energies in the work. One influences the other and vice versa. I try my best to balance them out. Some works focus more on religious symbolism, while others focus more on ancestral energy and mysticism. I try to keep both as part of my identity and my artistic identity. They are equally important for me and for the development of my practice, especially as I grow older and learn about different things. Even though I grew up more on the Catholic side, I have opened my eyes to other forms of faith and ways of understanding the world. Both of these aspects are explored in my works, depending on the painting itself. Overall, I would say there is a strong balance of the two in my artistic practice.

The figures in your work are monumental, colorful, and powerful. How do you understand the Caribbean body within your practice, and what do you aim to communicate through it about identity, beauty, and resistance?

I think the figures in my work are definitely the most important part of the work. I would say beyond the compositions, the figures themselves hold a lot of power. Even though they are made-up figures and characters from my imagination, they still have a sense of the Caribbean, whether it’s in their skin tone, their actions in the paintings, or the different features that I’ve created as part of their own world. But the Caribbean and Latin America are always at the core of their identity. I try to portray different body sizes and different versions of what a human being looks like, even though the figures themselves wouldn’t necessarily be considered human. They have different parts that make them unique in their own way. One of those things is the ears, the colorful ears that all the figures have, which is almost my way of keeping the Caribbean as part of their anatomy, like having the Caribbean be part of their identity through my own world-building. I think that’s a way of showing the beauty and uniqueness of the Caribbean and the things that make us who we are.

Your work reimagines historical and touristic images of the Caribbean. What do you seek to challenge or return to the viewer when they encounter these representations through your lens?

I think a big part of the work is to teach the general public or the viewer about the Caribbean in different ways. One side focuses more on the history of the Caribbean, how we ended up where we are and how we became who we are. It’s about the history of colonization, how the islands came to be, the history of the land, for example. I think having all those historical references gives the viewer a sense of where a lot of what you see in the work comes from. Then there’s also the more tourist-like, characteristic images of the Caribbean that are part of the DNA and natural landscape of the islands, which focus more on contemporary life. I think that shows the side of where we are today in the Caribbean. So for me, it’s important to have both contexts, the history, to understand where we came from and how things became what they are today, and also a sense of the present. If you’re someone from the islands, you can see your history and your people reflected in the work. And if you’re not familiar with the Caribbean, the work can teach you about it, that it’s more than just the tourist images or the carnival. There are so many different cultural elements that make the Caribbean unique. I think part of my goal is to showcase all these different sides of it, to represent the Caribbean in its fullest way, both the good things and the bad things that come with the islands.

You’ve exhibited your work in places as different as Shanghai, Boston, Miami, and New York. What do you discover through these cultural exchanges, and how does Dominican identity translate across such different contexts?

As my work has started to travel more internationally, it’s been really interesting to see how people from different parts of the world connect with it. I think Caribbean contemporary art hasn’t had as much presence in the global art world as it deserves, so a lot of audiences are still getting familiar with the kind of imagery and symbolism that I use. Showing the work in places like Shanghai, Europe, or Canada has been exciting, especially when I meet people from the diaspora who see themselves reflected in what I do, that’s always really special. The more the work reaches different places, the more I realize how little people actually know about the Caribbean and its culture. That’s why showing my work abroad feels so meaningful, it’s a chance to bring a bit of that world with me, to share Dominican and Caribbean identity in new spaces and see how people connect with it in their own way.

As a Dominican artist in the international contemporary scene, what kind of legacy do you hope to build? What message or ongoing conversation would you like to leave open for new generations of Caribbean and diasporic creators?

I think legacy is something really important to me, especially as a Dominican and Caribbean artist. Like I mentioned before, there hasn’t been much space for Caribbean contemporary art within the global art conversation, or even in art history when it comes to painting and sculpture. So part of what I hope to do is open doors for future generations of Caribbean artists who might feel misunderstood or unseen, whose stories haven’t been told yet. I also hope my work helps broaden the conversation around the Caribbean itself. It’s important that the region has a place in world history, and if my practice can contribute to that in any way, I’d be more than happy.

Leticia is a multidisciplinary creative and cultural strategist with 10+ years of experience leading impactful projects at the crossroads of art, design, tourism, and cultural heritage. As the founder and creative director of Afrohunting, Leticia centers Afro-descendant narratives through thoughtful, creative direction and intentional cultural curation.